Introduction

In this article, I am going to elaborate on the examples given in the second paragraph of the section 1.3.2 of [1]. These examples are about the comparison of causal relations with probabilistic relations from the perspective of stability.

Causal Relations Vs. Probabilistic Relations

Here is a summary of the information about causal relations and probabilistic relations in the second paragraph of the section 1.3.2. of [1]. Causal relations rely on objective physical constraints in the world. On the other hand, probabilistic relations are subjective. They depend on our belief in or knowledge about the world. Hence, causal relations are more stable and reliable than probabilistic relations. Causal relations stay unchanged unless the environment changes. How-ev-er, probabilistic relations vary as our belief in or knowledge about the en-vi-ron-ment changes.

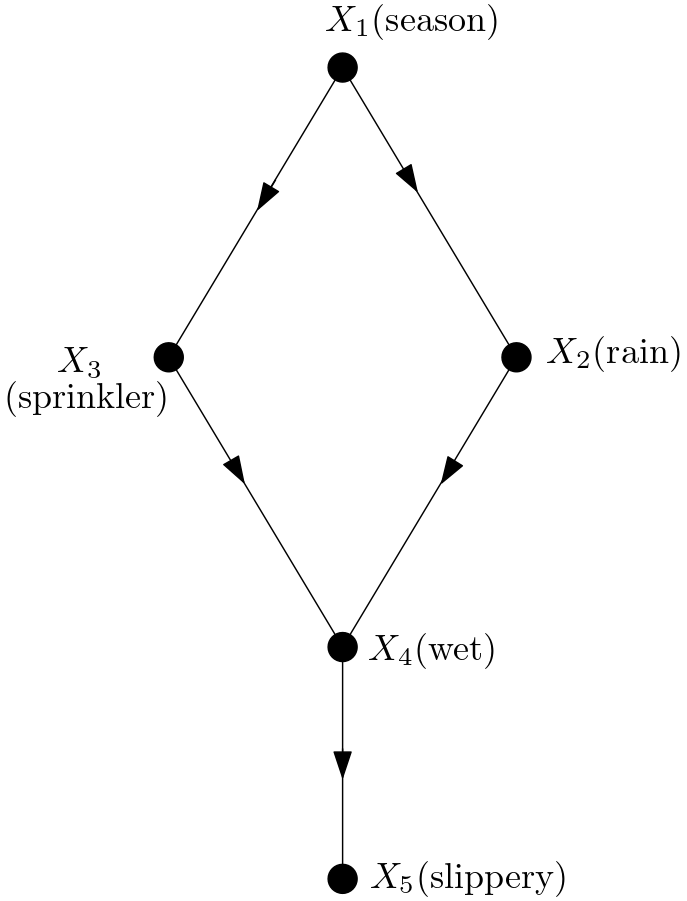

In order to give examples about causal relations and probabilistic relations, I am going to use a simple causal model. This model is defined in the section 1.2.2 of [1]. The features in this model are the season ($X_{1}$), the state of the rain ($X_{2}$), the state of the sprinkler ($X_{3}$), the wetness state of the pavement ($X_{4}$). The output of the model is whether the pavement is slippery or not ($X_{5}$). The directed acyclic graph (DAG) of this causal model is given in the Figure 1.

A causal relation is the following: “The state of the sprinkler does not affect the state of the rain”. A probabilistic relation can be stated as follows: “The state of the sprinkler is unassociated with the state of the rain”. Applying d-separation criteron on the DAG in the Figure 1, I am going to give some more details on the causality of the first statement. Then, I am going to elaborate on the change of the logic state (true or false) of the probabilistic statement depending on the information I have. Since I am going to use the d-separation criterion, let it be defined first. It is defined in Definition 1.2.3 in the section 1.2.3 of [1]. I am going to rewrite that definition from [1] as follows:

A path $p$ is said to be d-separated (or blocked) by a set of nodes $Z$ if and only if

-

$p$ contains a chain $i \rightarrow m \rightarrow j$ or a fork $i \leftarrow m \rightarrow j$ such that the middle node $m$ is in $Z$, or

-

$p$ contains an inverted fork (or collider) $i \rightarrow m \leftarrow j$ such that the middle node $m$ is not in $Z$ and such that no descendant of $m$ is in $Z$.

A set $Z$ is said to d-separate $X$ from $Y$ if and only if $Z$ blocks every path from a node in $X$ to a node in $Y$.

A path is a sequence of consecutive edges (of any directionaliy) in the graph.

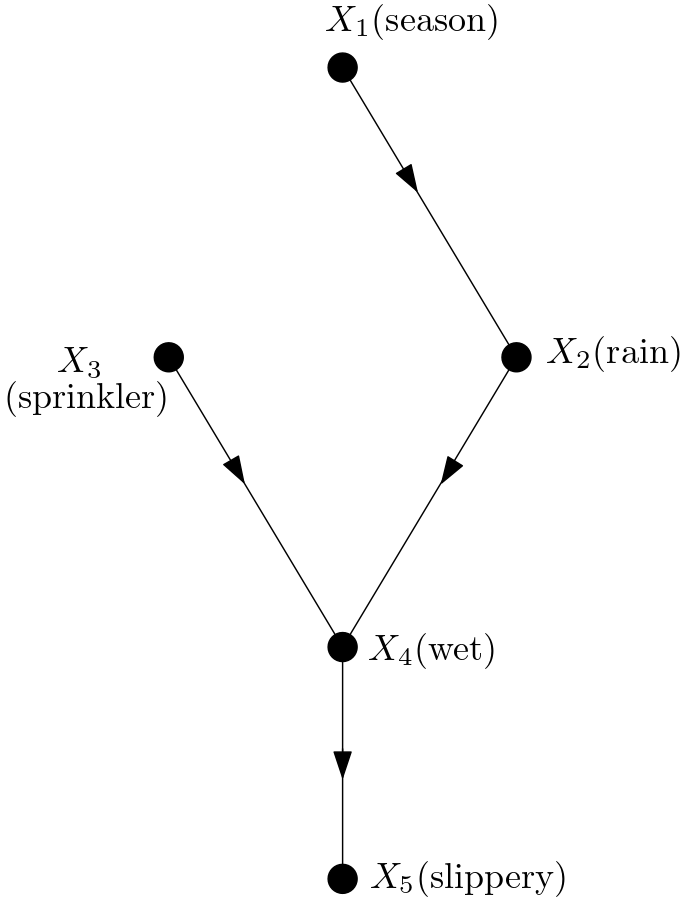

Let the causal relation “The state of the sprinkler does not affect the state of the rain” be verified using the d-separation criterion and the DAG in the Figure 1. In order to find the causal effect of the sprinkler on the rain, an intervention is made on the sprinkler. The intervention on the sprinkler is shown by the mutilated graph in the Figure 2.

According to the mutilated graph, $X_{2}$, $X_{3}$ and $X_{4}$ form the collider $X_{2} \rightarrow X_{4} \leftarrow X_{3}$ and there is no connection from $X_{3}$ to $X_{1}$. Then, $X_{3}$ is d-separated from $X_{2}$ in the mutilated graph. This means that the state of the sprinkler ($X_{3}$) does not affect the state of the rain ($X_{2}$) independently of whatever information I learn about the states of the variables in the DAG.

Now, let me give some more details about the probabilistic relation using the DAG in the Figure 1 and the d-separation criterion. The probabilistic relation has been stated to be “the state of the sprinkler is unassociated with the state of the rain”. According to the DAG in the Figure 1, this statement is wrong. The reason is that the state of the sprinkler ($X_{3}$) is associated with the state of the rain ($X_{2}$) due to the fork $X_{3} \leftarrow X_{1} \rightarrow X_{2}$. Let me indicate how the logical state of this probabilistic statement changes with the information I have. Let me assume that I learn which season we are in. Then, $X_{1}$ is known and according to the d-separation criterion, the path $X_{3} \leftarrow X_{1} \rightarrow X_{2}$ is blocked by $X_{1}$. So, when I learn the season I am in, the state of the sprinkler ($X_{3}$) becomes unassociated with the state of the rain ($X_{2}$). The logical state of the probabilistic statement turns from false to true when I learn the information about the season. Let me assume that I also learn that the pavement is wet. Now, I know both the state of the season ($X_{1}$) and the state of the pavement ($X_{4}$). When I learn the state of the pavement ($X_{4}$), the path $X_{3} \rightarrow X_{4} \leftarrow X_{2}$ is unblocked although the path $X_{3} \leftarrow X_{1} \rightarrow X_{2}$ is still blocked by $X_{1}$. Now, the state of the sprinkler ($X_{3}$) is associated with the state of the rain ($X_{2}$). As my knowledge changes, the probabilistic relation’s logical value changes from false to true and then from true to false.

Conclusion

The difference between a causal relation and a probabilistic relation has been shown using the DAG for a causal model and the d-separation criterion. A causal relation holds independently of the knowledge about or belief in the environment whereas a probabilistic relation’s truth value changes with the changes in the knowledge about or belief in the environment.

References

[1] Judea Pearl, Causality: Models, Reasoning and Inference, Cambridge University Press, 2009.